Delusions

Our brains create every color smell taste sound physical sensation emotion thing we experience.

Length 1:11:32 | Sept. 27 2019

Beau Lotto Neuroscientist | Anil Seth Neuroscientist | Christine Constantinople Neuroscientist | Donald Hoffman Cognitive Scientist | Stavros Lomvardas Neuroscientist

Your eyes and ears don’t tell you the truth. That’s not what they’re for. The senses evolved to enable us to survive and succeed in the world, not to represent it accurately. Now, for the first time, science is revealing exactly how the sense organs receive information, process it, and pass it to the brain, providing deep insight into why we experience the world the way we do—and what it might be like for future technology to transform such experiences, perhaps allowing us to see infrared light or feel magnetic north. Join an eminent group of neuroscientists and philosophers for an ear, tongue, nose and eye-opening adventure that challenges everything we experience in search of the true nature of reality.

ARTICLES & ESSAYS

Two papers released in Neuron delve deep into the way we perceive the world, revealing that we don’t actually register much of it.

The Atlantic | Ed Yong

…brains are special because of the behavior they create—everything from a predator’s pounce to a baby’s cry. But the study of such behavior is being de-prioritized, or studied “almost as an afterthought.”

Narratively | Alaina Leary

What it’s like to live with a disorder that means sometimes I can’t even recognize my own family members—and why I’m not keeping it a secret any longer.

- Researchers took body odour samples from 30 heterosexual Scottish couples

- They then got volunteers to smell paired odour samples and rank the similarities

- Couples were perceived as naturally smelling similar than random pairings did

- Use of similar-smelling fragranced deodorants did not have an effect, however

- Unlike women, men appear happier with partners who smell more like them

ZOE SCHIFFER, BUSINESS INSIDER

…online shopping sites use coercive so-called “dark pattern” techniques to trick people into spending more money.

“This is manipulating users into making decisions they wouldn’t otherwise make and buying stuff they don’t need,” Gunes Acar, a research associate at Princeton who helped run the study, told Business Insider.

The Atlantic |Matthieu Ricard and Wolf Singer

A scientist and a monk compare notes on meditation, therapy, and their effects on the brain.

Video

Face Blindness – Oliver Sacks – Length 1:58 | Jan 17 2016

Neurologist and writer Oliver Sacks suffers from a rare neurological condition called prosopagnosia, also known as face blindness.

Sensation Without Perception – Length 3:31 | Aug 2009

Short clip of a woman with prosopagnosia—the inability to recognize faces.

How being Face-Blind made it easier to see people – Length 13:02 | Feb 16, 2019

Fleassy has a condition that makes it impossible to remember faces. How would you life your life if you didn’t recognise the ones you know and love?

Length 18:45 | Sep 18 2009

Neurologist and author Oliver Sacks brings our attention to Charles Bonnett syndrome — when visually impaired people experience lucid hallucinations. He describes the experiences of his patients in heartwarming detail and walks us through the biology of this under-reported phenomenon.

Length 58:31 | Aug 6, 2012

Neurologist Oliver Sacks discusses his book, “The Mind’s Eye,” with author Cullen Murphy.

In his book, “The Mind’s Eye,” he “tells the stories of people who are able to navigate the world and communicate with others despite losing what many of us consider indispensable senses and abilities: the power of speech, the capacity to recognize faces, the sense of three-dimensional space, the ability to read, the sense of sight. For all of these people, the challenge is to adapt to a radically new way of being in the world.”

Behaviour Hypnosis

ARTICLES & ESSAYS

It’s a question that’s reverberated through the ages – are humans, though imperfect, essentially kind, sensible, good-natured creatures? Or are we, deep down, wired to be bad, blinkered, idle, vain, vengeful and selfish? There are no easy answers, and there’s clearly a lot of variation between individuals, but here we shine some evidence-based light on the matter through 10 dispiriting findings that reveal the darker and less impressive aspects of human nature:

We view minorities and the vulnerable as less than human. One striking example of this blatant dehumanization came from a brain-scan study that found a small group of students exhibited less neural activity associated with thinking about people when they looked at pictures of the homeless or of drug addicts, as compared with higher-status individuals. Another study showed that people who are opposed to Arab immigration tended to rate Arabs and Muslims as literally less evolved than average. Among other examples, there’s also evidence that young people dehumanise older people; and that men and women alike dehumanise drunk women. What’s more, the inclination to dehumanise starts early – children as young as five view out-group faces (of people from a different city or a different gender to the child) as less human than in-group faces.

We experience Schadenfreude (pleasure at another person’s distress) by the age of four, according to a study from 2013. That sense is heightened if the child perceives that the person deserves the distress. A more recent study found that, by age six, children will pay to watch an antisocial puppet being hit, rather than spending the money on stickers.

We believe in karma – assuming that the downtrodden of the world deserve their fate. The unfortunate consequences of such beliefs were first demonstrated in the now classic research from 1966 by the American psychologists Melvin Lerner and Carolyn Simmons. In their experiment, in which a female learner was punished with electric shocks for wrong answers, women participants subsequently rated her as less likeable and admirable when they heard that they would be seeing her suffer again, and especially if they felt powerless to minimise this suffering. Since then, research has shown our willingness to blame the poor, rape victims, AIDS patients and others for their fate, so as to preserve our belief in a just world. By extension, the same or similar processes are likely responsible for our subconscious rose-tinted view of rich people.

We are blinkered and dogmatic. If people were rational and open-minded, then the straightforward way to correct someone’s false beliefs would be to present them with some relevant facts. However a classic study from 1979 showed the futility of this approach – participants who believed strongly for or against the death penalty completely ignored facts that undermined their position, actually doubling-down on their initial view. This seems to occur in part because we see opposing facts as undermining our sense of identity. It doesn’t help that many of us are overconfident about how much we understand things and that, when we believe our opinions are superior to others, this deters us from seeking out further relevant knowledge.

We would rather electrocute ourselves than spend time in our own thoughts. This was demonstrated in a controversial 2014 study in which 67 per cent of male participants and 25 per cent of female participants opted to give themselves unpleasant electric shocks rather than spend 15 minutes in peaceful contemplation.

We are vain and overconfident. Our irrationality and dogmatism might not be so bad were they married to some humility and self-insight, but most of us walk about with inflated views of our abilities and qualities, such as our driving skills, intelligence and attractiveness – a phenomenon that’s been dubbed the Lake Wobegon Effect after the fictional town where ‘all the women are strong, all the men are good-looking, and all the children are above average’. Ironically, the least skilled among us are the most prone to overconfidence (the so-called Dunning-Kruger effect). This vain self-enhancement seems to be most extreme and irrational in the case of our morality, such as in how principled and fair we think we are. In fact, even jailed criminals think they are kinder, more trustworthy and honest than the average member of the public.

We are moral hypocrites. It pays to be wary of those who are the quickest and loudest in condemning the moral failings of others – the chances are that moral preachers are as guilty themselves, but take a far lighter view of their own transgressions. In one study, researchers found that people rated the exact same selfish behaviour (giving themselves the quicker and easier of two experimental tasks on offer) as being far less fair when perpetuated by others. Similarly, there is a long-studied phenomenon known as actor-observer asymmetry, which in part describes our tendency to attribute other people’s bad deeds, such as our partner’s infidelities, to their character, while attributing the same deeds performed by ourselves to the situation at hand. These self-serving double standards could even explain the common feeling that incivility is on the increase – recent research shows that we view the same acts of rudeness far more harshly when they are committed by strangers than by our friends or ourselves.

We are all potential trolls. As anyone who has found themselves in a spat on Twitter will attest, social media might be magnifying some of the worst aspects of human nature, in part due to the online disinhibition effect, and the fact that anonymity (easy to achieve online) is known to increase our inclinations for immorality. While research has suggested that people who are prone to everyday sadism (a worryingly high proportion of us) are especially inclined to online trolling, a study published last year revealed how being in a bad mood, and being exposed to trolling by others, double the likelihood of a person engaging in trolling themselves. In fact, initial trolling by a few can cause a snowball of increasing negativity, which is exactly what researchers found when they studied reader discussion on CNN.com, with the ‘proportion of flagged posts and proportion of users with flagged posts … rising over time’.

We favour ineffective leaders with psychopathic traits. The American personality psychologist Dan McAdams recently concluded that the US President Donald Trump’s overt aggression and insults have a ‘primal appeal’, and that his ‘incendiary Tweets’ are like the ‘charging displays’ of an alpha male chimp, ‘designed to intimidate’. If McAdams’s assessment is true, it would fit into a wider pattern – the finding that psychopathic traits are more common than average among leaders. Take the survey of financial leaders in New York that found they scored highly on psychopathic traits but lower than average in emotional intelligence. A meta-analysis published this summer concluded that there is indeed a modest but significant link between higher trait psychopathy and gaining leadership positions, which is important since psychopathy also correlates with poorer leadership.

We are sexually attracted to people with dark personality traits. Not only do we elect people with psychopathic traits to become our leaders, evidence suggests that men and women are sexually attracted, at least in the short term, to people displaying the so-called ‘dark triad’ of traits – narcissism, psychopathy and Machiavellianism – thus risking further propagating these traits. One study found that a man’s physical attractiveness to women was increased when he was described as self-interested, manipulative and insensitive. One theory is that the dark traits successfully communicate ‘mate quality’ in terms of confidence and the willingness to take risks. Does this matter for the future of our species? Perhaps it does – another paper, from 2016, found that those women who were more strongly attracted to narcissistic men’s faces tended to have more children.

Don’t get too down – these findings say nothing of the success that some of us have had in overcoming our baser instincts. In fact, it is arguably by acknowledging and understanding our shortcomings that we can more successfully overcome them, and so cultivate the better angels of our nature.

This is an adaptation of an article originally published by The British Psychological Society’s Research Digest.

The Atlantic | Ben Yagoda

Science suggests we’re hardwired to delude ourselves. Can we do anything about it?

Overcoming procrastination isn’t so much about completing tasks. In reality, it’s about something much more personal.

New research suggests that over thousands of years of dog domestication, people preferred pups that could pull off that appealing, sad look. And that encouraged the development of the facial muscle that creates it.

“The implications are quite profound,” said Brian Hare from Duke University…

There’s what feels right and then there’s what is right, and they aren’t always the same.

Beauty

Video

Length 9:42 | Aug 18, 2018

The video is set to start at 5:09 where the hypnotist implants the belief that he is Leonardo Di Caprio.

Length 14:48 | Aug 22 2017

Anjan Chatterjee uses tools from evolutionary psychology and cognitive neuroscience to study one of nature’s most captivating concepts: beauty. Learn more about the science behind why certain configurations of line, color and form excite us in this fascinating, deep look inside your brain.

ARTICLES & ESSAYS

Ed Yong summarizes a new investigation into the neural substrate of beauty:

Tomohiro Ishizu and Semir Zeki from University College London watched the brains of 21 volunteers as they looked at 30 paintings and listened to 30 musical excerpts. All the while, they were lying inside an fMRI scanner, a machine that measures blood flow to different parts of the brain and shows which are most active. The recruits rated each piece as “beautiful”, “indifferent” or “ugly”.

The scans showed that one part of their brains lit up more strongly when they experienced beautiful images or music than when they experienced ugly or indifferent ones – the medial orbitofrontal cortex or mOFC.

Several studies have linked the mOFC to beauty, but this is a sizeable part of the brain with many roles. It’s also involved in our emotions, our feelings of reward and pleasure, and our ability to make decisions. Nonetheless, Ishizu and Zeki found that one specific area, which they call “field A1” consistently lit up when people experienced beauty.

The images and music were accompanied by changes in other parts of the brain as well, but only the mOFC reacted to beauty in both forms. And the more beautiful the volunteers found their experiences, the more active their mOFCs were. That is not to say that the buzz of neurons in this area produces feelings of beauty; merely that the two go hand-in-hand.

On the one hand, it’s not exactly shocking that beauty can be sourced to the cortex. Where else would it be? Like disgust or delight, beauty is a visceral emotion, a pleasure that Nabokov described as being synonymous with “the the sudden erection of your small dorsal hairs.” That beauty can be localized to the mOFC only reminds us that it’s part of the pleasure spectrum, since that brain area has consistently been implicated in the recognition of delightful things, from the taste of an expensive wine to the luxurious touch of cashmere.

But why does beauty exist? What’s the point of marveling at a Rembrandt self portrait or a Bach fugue? To paraphrase Auden, beauty makes nothing happen. Unlike our more primal indulgences, the pleasure of perceiving beauty doesn’t ensure that we consume calories or procreate. Rather, the only thing beauty guarantees is that we’ll stare for too long at some lovely looking thing. Museums are not exactly adaptive.

Here’s my (extremely speculative) theory: Beauty is a particularly potent and intense form of curiosity. It’s a learning signal urging us to keep on paying attention, an emotional reminder that there’s something here worth figuring out. Art hijacks this ancient instinct: If we’re looking at a Rothko, that twinge of beauty in the mOFC is telling us that this painting isn’t just a blob of color; if we’re listening to a Beethoven symphony, the feeling of beauty keeps us fixated on the notes, trying to find the underlying pattern; if we’re reading a poem, a particularly beautiful line slows down our reading, so that we might pause and figure out what the line actually means. Put another way, beauty is a motivational force that helps modulate conscious awareness. The problem beauty solves is the problem of trying to figure out which sensations are worth making sense of and which ones can be easily ignored.

Let’s begin with the neuroscience of curiosity, that weak form of beauty. There’s an interesting recent study from the lab of Colin Camerer at Caltech, led by Min Jeong Kang. The experiment itself was straightforward: Nineteen Caltech undergrads were asked 40 trivia questions while in a brain scanner. After reading each question, the subjects were told to silently guess the answer, and to indicate their curiosity about the correct answer. Then, they saw the question presented again, followed by the correct answer.

The first thing the scientists discovered is that curiosity obeys an inverted U-shaped curve, so that we’re most curious when we know a little about a subject (our curiosity has been piqued) but not too much (we’re still uncertain about the answer). This supports the information gap theory of curiosity, which was first developed by George Loewenstein of Carnegie-Mellon in the early 90s. According to Loewenstein, curiosity is rather simple: It comes when we feel a gap “between what we know and what we want to know”. This gap has emotional consequences: it feels like a mental itch. We seek out new knowledge because we that’s how we scratch the itch.

The fMRI data nicely extended this information gap model of curiosity. It turns out that, in the moments after the question was first asked, subjects showed a substantial increase in brain activity in three separate areas: the left caudate, the prefrontal cortex and the parahippocampal gyri. The most interesting finding is the activation of the caudate, which seems to sit at the intersection of new knowledge and positive emotions. (For instance, the caudate has been shown to be activated by various kinds of learning that involve feedback, while it’s also been closely linked to various parts of the dopamine reward pathway.) The lesson is that our desire for more information – the cause of curiosity – begins as a dopaminergic craving, rooted in the same primal pathway that responds to sex, drugs and rock and roll.

I see beauty as a form of curiosity that exists in response to sensation, and not just information. It’s what happens when we see something and, even though we can’t explain why, want to see more. But here’s the interesting bit: the hook of beauty, like the hook of curiosity, is a response to an incompleteness. It’s what happens when we sense something missing, when there’s a unresolved gap, when a pattern is almost there, but not quite. I’m thinking here of that wise Leonard Cohen line: “There’s a crack in everything – that’s how the light gets in.” Well, a beautiful thing has been cracked in just the right way.

The best way to reveal the link between curiosity and beauty is with music. Why do we perceive certain musical sounds as beautiful? On the one hand, music is a purely abstract art form, devoid of language or explicit ideas. The stories it tells are all subtlety and subtext; there is no content to get curious about. And yet, even though music says little, it still manages to touch us deep, to tittilate some universal dorsal hairs.

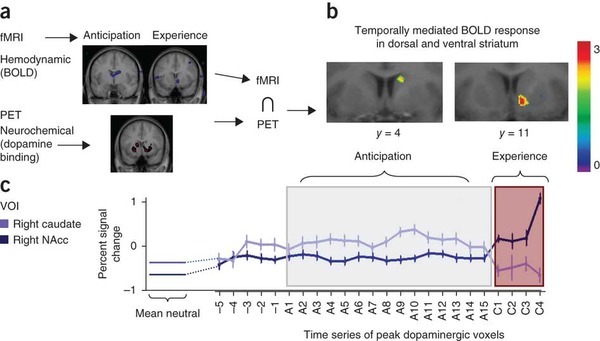

We can now begin to understand where these feelings come from, why a mass of vibrating air hurtling through space can trigger such intense perceptions of beauty. Consider this recent paper in Nature Neuroscience by a team of Montreal researchers. Although the study involves plenty of fancy technology, including fMRI and ligand-based positron emission tomography (PET) scanning, the experiment itself was rather straightforward. After screening 217 individuals who responded to advertisements requesting people that experience “chills to instrumental music,” the scientists narrowed down the subject pool to ten. (These were the lucky few who most reliably got chills.) The scientists then asked the subjects to bring in their playlist of favorite songs – virtually every genre was represented, from techno to tango – and played them the music while their brain activity was monitored.

Because the scientists were combining methodologies (PET and fMRI) they were able to obtain a precise portrait of music in the brain. The first thing they discovered (using ligand-based PET) is that beautiful music triggers the release of dopamine in both the dorsal and ventral striatum. This isn’t particularly surprising: these regions have long been associated with the response to pleasurable stimuli. The more interesting finding emerged from a close study of the timing of this response, as the scientists looked to see what was happening in the seconds before the subjects got the chills.

I won’t go into the precise neural correlates – let’s just say that you should thank your right nucleus accumbens the next time you listen to your favorite song – but want to instead focus on an interesting distinction observed in the experiment:

In essence, the scientists found that our favorite moments in the music – those sublimely beautiful bits that give us the chills – were preceeded by a prolonged increase of activity in the caudate, the same brain area involved in curiosity. They call this the “anticipatory phase,” as we await the arrival of our favorite part:

Immediately before the climax of emotional responses there was evidence for relatively greater dopamine activity in the caudate. This subregion of the striatum is interconnected with sensory, motor and associative regions of the brain and has been typically implicated in learning of stimulus-response associations and in mediating the reinforcing qualities of rewarding stimuli such as food.

In other words, the abstract pitches have become a primal reward cue, the cultural equivalent of a bell that makes us drool. Here is their summary:

The anticipatory phase, set off by temporal cues signaling that a potentially pleasurable auditory sequence is coming, can trigger expectations of euphoric emotional states and create a sense of wanting and reward prediction. This reward is entirely abstract and may involve such factors as suspended expectations and a sense of resolution. Indeed, composers and performers frequently take advantage of such phenomena, and manipulate emotional arousal by violating expectations in certain ways or by delaying the predicted outcome (for example, by inserting unexpected notes or slowing tempo) before the resolution to heighten the motivation for completion.

The question, of course, is what all these dopamine neurons in the caudate are up to. What aspects of music are triggering those chills, that visceral perception of beauty? And why are these cells so active fifteen seconds before the acoustic climax? After all, we typically associate surges of dopamine with pleasure, with the processing of actual rewards. And yet, this cluster of cells in the caudate is most active when the melodic pattern is still unresolved, when the musical pattern is still incomplete.

One way to answer these questions is to zoom out, to look at the music and not the neuron. While music can often seem (at least to the outsider) like an intricate pattern of pitches – it’s art at its most mathematical – it turns out that the most important part of every song or symphony is when the patterns break down, when the sound becomes unpredictable. If the music is too obvious, it is annoyingly boring, like an alarm clock. (Numerous studies, after all, have demonstrated that dopamine neurons quickly adapt to predictable rewards. If we know what’s going to happen next, then we don’t get excited.) This is why composers introduce the tonic note in the beginning of the song and then studiously avoid it until the end. They want to make us curious, to create a beautiful gap between what we hear and what we want to hear.

To demonstrate this psychological principle, the musicologist Leonard Meyer, in his classic book Emotion and Meaning in Music (1956), analyzed the 5th movement of Beethoven’s String Quartet in C-sharp minor, Op. 131. Meyer wanted to show how music is defined by its flirtation with – but not submission to – our expectations of order. To prove his point, Meyer dissected fifty measures of Beethoven’s masterpiece, showing how Beethoven begins with the clear statement of a rhythmic and harmonic pattern and then, in an intricate tonal dance, carefully avoids repeating it. What Beethoven does instead is suggest variations of the pattern. He is its evasive shadow. If E major is the tonic, Beethoven will play incomplete versions of the E major chord, always careful to avoid its straight expression. He wants to preserve an element of uncertainty in his music, making our brains exceedingly curious for the one chord he refuses to give us. Beethoven saves that chord for the end.

According to Meyer, it is the suspenseful tension of music (arising out of our unfulfilled expectations) that is the source of the music’s beauty. While earlier theories of music focused on the way a noise can refer to the real world of images and experiences (its “connotative” meaning), Meyer argued that the emotions we find in music come from the unfolding events of the music itself. This “embodied meaning” arises from the patterns the symphony invokes and then ignores, from the ambiguity it creates inside its own form. “For the human mind,” Meyer writes, “such states of doubt and confusion are abhorrent. When confronted with them, the mind attempts to resolve them into clarity and certainty.” And so we wait, expectantly, for the resolution of E major, for Beethoven’s established pattern to be completed. This nervous anticipation, says Meyer, “is the whole raison d’etre of the passage, for its purpose is precisely to delay the cadence in the tonic.” The uncertainty – that crack in the melody – makes the feeling.

What I like about this speculation is that it begins to explain why the feeling of beauty is useful. The aesthetic emotion might have begun as a cognitive signal telling us to keep on looking, because there is a pattern here that we can figure out it. In other words, it’s a sort of a metacognitive hunch, a response to complexity that isn’t incomprehensible. Although we can’t quite decipher this sensation – and it doesn’t matter if the sensation is a painting or a symphony – the beauty keeps us from looking away, tickling those dopaminergic neurons and dorsal hairs. Like curiosity, beauty is a motivational force, an emotional reaction not to the perfect or the complete, but to the imperfect and incomplete. We know just enough to know that we want to know more; there is something here, we just don’t what. That’s why we call it beautiful.

Mass Hypnosis

ARTICLES & ESSAYS

Mass psychogenic illness (MPI), also called mass sociogenic illness, mass psychogenic disorder, epidemic hysteria, or mass hysteria, is “the rapid spread of illness signs and symptoms affecting members of a cohesive group, originating from a nervous system disturbance involving excitation, loss, or alteration of function, whereby physical complaints that are exhibited unconsciously have no corresponding organic aetiology”.

Genetic Hypnosis

ARTICLES & ESSAYS

Mental Floss | Sophie Harrington, Mark Manson

…recent studies have found specific genetic differences associated with the taste. A study by the personal genomics company 23andMe identified a small DNA variation in a cluster of olfactory receptor genes that is strongly associated with the perception of a “soapy” taste in cilantro.

Harvard Business Review | Margarita Mayo

The research is clear: when we choose humble, unassuming people as our leaders, the world around us becomes a better place.

Yet instead of following the lead of these unsung heroes, we select negative charismatic leaders; high arrogant authoritarianism and high narcissism.

We are hardwired to search for romanticized superheroes: over-glorifying leaders who exude charisma.